I belong to the generation that was terrified at the sound of the word “dropout”.

From very early in life we were taught to always finish what we started, regardless if this was an overloaded lunch at the family table, the book we got as present from auntie Mary or a boring class. Leaving a task unfinished was a major failure, not to mention dropouts from school, who were in general perceived as losers, sad examples of what happens when you miss focus and persistence, exactly what you should avoid if you are to succeed in life.

Then later on came the new economy or so , headlines filled with glorified dropouts, people like Steve Jobs, Bill Gates or Mark Zuckerberg who dropped out of College to create Empires and Unicorns and then suddenly the possibility occurred that dropping out of University did not necessarily implied a life of shame and misery. On the contrary, people like myself who graduated only to find that completion of studies usually meant a decade of modest finances and a career start with a significant debt, seriously doubted the advice they received as teenagers.

But my intension today is not to discuss the merits of completing a University programme or the chances of becoming a glorified hero of the new economy. The reason I write these lines is to help myself clarify what is the purpose and value of “course completion” in the new learning economy of on-line learning, on-demand education and Massive Open Online Courses.

The reason I write these lines is to help myself clarify what is the purpose and value of “course completion” in the new learning economy of on-line learning, on-demand education and Massive Open Online Courses.Back in the year 1999, in one of my very first papers as a young and curious PhD candidate, I concluded that distance learning was “plagued by a high drop out rate” (1). What I meant back then was that very few students actually finish what they started when it comes to not face-to-face courses. Back then “not face-to-face” courses implied a wide diversity of methodologies and technologies, from cassette recorded seminars, correspondence courses, television, diskettes and a pioneer internet virtual classrooms with 28 students which relied on 120 KB websites and CD-ROMs sent over the post (2). In particular of the later, we were proud to report back then that most of the students who started the course, were actually “there” (online, at the Internet Relay Chat network) when we finished it (3). Almost twenty years fast forward in 2019 and our 5-week virtual classroom enrolled more than 30,000 students in two years, only this time it was a “MOOC” or Massive Open Online Classroom. Much has changed in the meanwhile, technology, US presidents, student generations, teaching paradigms, you name it…but one things still there, our own, private beans-counting at the end of class…

Regardless if you teach a 25 students in a class or a 30,000 in a MOOC, there is a universal teacher question that always comes up: “How did we go with this course?”.

This time, there is a large pool of data to try to fish the answer from, student ratings, learners’ feedback and stories and a long series of metrics. Regardless of the variety of metrics however, there is still one that dominates our understanding: the all-time-classic Completion rate. Fine, you enrolled thousands in the course, but how many did you “graduate”? And what does it say about a course if only 5 or 10 % of the students actually completed it?

In such a question that is as old as education itself, lies the preconception of a merciless and inflexible duality: your students can either be “completers” or “drop-outs”. Consequently, a course that produces so many “drop-outs” must be in essence fundamentally flawed, even if it is a glorified e-learning innovation.

This brings me back a memory from my undergraduate years, the time we would also write our name in a small piece of paper and give it to the lecturer in the amphitheatre just before the start of the lecture. Beans counting again, only this time with a major, clear impact: You don’t have enough beans at the end of the semester, sorry, you just have to come back!

It doesn’t matter what you do in the amphitheatre, you can sleep, you can doodle, you can think of life, the Universe and everything, or you can just daydream, as long as you are there. Maybe even the physical presence is not necessary, as long as you can sneak out from the back doors sometime after the lights dim. This fundamental requirement for physical presence (regardless of any evidence of intellectual presence) is something that has haunted me as of today. No matter the framework, I will never-ever force anyone to be physically present at my seminars.

But that was a definition of a “teacher-centred” learning environment and I say that without any hint of judgement or criticism. It was a learning experience completely constructed and validated by the teacher. The teacher knows what you need to know, what you should be able to do in the end and how to get you there. Just follow the path, lecture after lecture, tutorial after tutorial, study the book, take the exam. Do this and there you are, delivered at the end of the semester, one step closer to being a doctor. Do this not and you will be a drop out. This has worked for centuries and it still works on, more or less, and I am not saying that there is something necessarily wrong with this. But this is not a MOOC.

A MOOC, on the other hand is the definition of a “student-centred” learning environment. A Teacher or a team of teachers has constructed a learning environment, but how this environment will be navigated is now completely up to the individual students, who might end up with very different learning experiences.

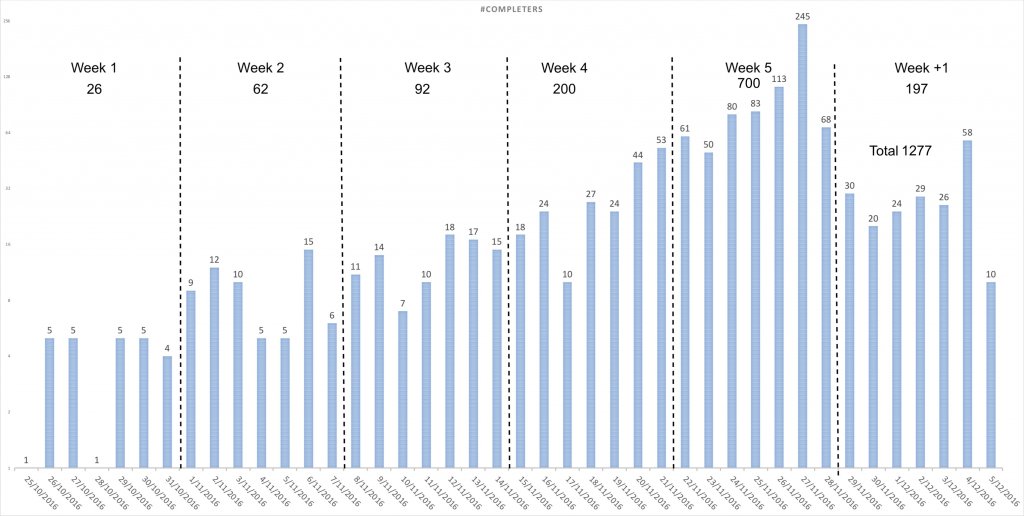

To illustrate this a bit better, I would call on our experience with our MOOC in Implant Dentistry. We recently completed analysing the clickstreams from the first run of the MOOC in 2016, a run that attracted more than 7,000 learners in a course that was meant to last for 5 weeks (4). As with every course we have run in the past, there was a “prescribed” pathway, that is a linear progression from A to Z, which was constructed by the teacher, aiming to escort the learners in a progressive discovery of the topic, unlocking some critical competences on the way. The prescribed journey was meant to last five weeks and I envisioned a gradual journey hand in hand with my seven thousand students, finishing off with an on-line completion, digital graduation, a cool pdf certificate and virtual champagne popping.

Is this what happened in the end? Well not really, or not exactly to be precise. The course received very high ratings and a lot of praise from many learners all over the world. But it was about 25 % only of the learners that got to complete the course and even so, they did it in a very individual timeframe!

Studying the clickstream, we could see that only 28 % or the active learners followed a more or less linear pathway, while 72 % didn’t.

We called the first group “attentive” while the second “auditors”. “Attentive” learners were much more likely to follow the teacher-prescribed learning pathway, achieved higher grades and 83 % completed the course and purchased a certificate. On the other hand, the non-linear “auditors”, took less exams, while no more than 3 % completed the course. Nevertheless, they demonstrated engagement with the content and activities, albeit not in its entirety and many actually.

And here comes the tricky part of trying to make sense of the whole picture and assess the learning experience. In a conventional teacher-centred environment, one could be tempted to speak of a 25% completers , 75 % dropouts and a course with 25% completion rate. The reality however reflected by the study of the clickstream is very different.

A course of these proportions on a clinical discipline will inevitably attract a large and diverse audience of learners. Some will be still in their undergraduate studies seeking an overall understanding of the topic, while others will be postgraduates, specialising in one narrow field of Implant Dentistry. Many will be already practicing clinicians, already at diverse levels and scope of practice of implant dentistry. Finally, some others might be not clinicians, but scientists within related fields, representatives of the industry, medical engineers, dental technicians. The course had something for all, but not all were interested in attending the complete course. Inevitably, in a crowd of 30,000 learners, people have different objectives and different reasons to enrol in the course. Some came to follow the teaching of a specific speaker they admired, others to update themselves in a technique and topic they practice, others to have a sneak peek into the latest scientific updates. And the MOOC, being first and foremost a student-centred environment allowed them to get what they were looking for at the minimum cost of time and effort. These students did not drop out in my mind. They came and took what they needed and then they simply chose to “graduate themselves”, probably the ultimate right in a student-centred learning environment.

So, with the experience we have acquired by now, I would have to seriously revise the statement of my 1998 publication: low completion rates is not a plague, but might even be a blessing, to the extent that it points out to a true student-centred learning experience. Completion of a course remains a teacher-defined metric and might be a valid measure of success to the extent that the teacher can correctly define the learning needs of the student. In a Massive Open environment however, this is simply impossible. Completion will only apply to a small number of students, usually novice in the topic, while a large segment of still active learners will seek to cater to their own specific needs. And this should be seen as a deficiency or failure of the course, on the contrary this might be a new significant strength of the MOOCs, which can create a flexible learning environment and accommodate diversity.

Conclusively, yet again educational technology has outgrown our teaching paradigms and we are in urgent need of new tools to assess the quality and impact of MOOCs and consequently to improve teaching and learning with such media. Completion rates will always be a benchmark for assessing a course, but relying only on old tools when assessing new learning environments will miss significant potential and can lead to misunderstanding and confusion. We need some out of the box thinking to go beyond the old dichotomous separation of completers and drop-outs and allow the true student-learning environments to demonstrate the whole range of colours and shades they can capture!

4 thoughts on ““Attentive”, “Auditors”, “Diggers”, “Browsers” and other online learning tribes..!”

Good ideas. Didn’t think from this point of view before. Thanks 🙂

Thank you for your kind feedback! Hopefully, we will soon have more!

Hello! I’m at work surfing around your blog from my new iphone!

Just wanted to say I love reading through your blog and look

forward to all your posts! Carry on the outstanding work!

Thank you for your kind comments and feedback! Nikos